November 08, 2022

![]() 13 mins Read

13 mins Read

Oh. You’re kidding. She’s about 24, honey blonde and beautiful. With a cute wink, a dip of the aviator shades and a flick of the waist-length ponytail, she takes my bag and stuffs it in the ‘boot’ (aka the tiny hatch beside the passenger door).

“Are you our pilot?” my travel companion stutters.

I gulp, awaiting the response. “Sure am,” replies Sarah, chipper as hell.

And breathe.

I don’t know about you, but light aircraft? Mmm, no thanks. Then again, I’ve been living in Darwin for a year and word on the street is this: a day trip to the Tiwi Islands to see the art and artists who live there is a no-brainer. It’s splendid, but a bruiser to get to.

Unfortunately, if you’ve got a penchant for a) art, b) fishing or c) Aussie Rules – and I’m 100 per cent ‘a’, with the empty wallet to prove it – then said splendour is absolutely, scientifically, 100 per cent unmissable.

Since arriving in the Northern Territory, I’ve gone softer than peach sorbet over the Aboriginal art lining the local tourist galleries. For the most part, the NT’s output is throbbing with colour and intricate networks of arcs, lines and dots.

An artist applies ‘dots’ to an artwork with a comb. (Image: Quentin Long)

But here’s the bother: the same artists crop up again and again. And not just on canvas, but on platters, key rings, diaries, pencils and neoprene beer holders.

That’s why Tiwi holds such caché. The art scene there, much like the location itself, is for purists.

There are the finer details: such as the fact Tiwi artists don’t use acrylics (just ochre paints) and much local work is based on body painting patterns, called ‘jilamara’. But there’s also the hefty logistical hurdler – so I’ve joined a Tiwi Islands art tour for the day.

To get there, you have to want it.

Until not long ago, a public ferry carted people to and from this network of 11 islands, around 80 kilometres north of Darwin. But that option has since been canned, leaving only a handful of alternatives: organise a private art-buying trip through the Tiwi Art Network, or jump on a tour with AAT Kings.

In short, you can’t easily do Tiwi under your own steam. And you can’t easily dodge the small plane scenario, either.

This explains why I’m braving the ‘scaredy-cat’ seat, right next to our gorgeous young pilot, many feet above croc-infested waters. Though once the islands creep into view, the soundtrack of chattering teeth swiftly fades.

We lean from our seats to see spearmint rivers, fields of iridescent green and vast sweeps of fern trees, which from the air, look like the tops of household dusters – the 1950s kind, with long, loose feathers.

“You won’t spot any kangaroos or wallabies here,” says Sarah at the wheel. Impressively though, and unlike mainland NT, frilled-necked lizards abound (blame and shame the cane toad for the depletion of the lizard population in other parts of the Territory).

“But there are wild brumbies and loads of birds.” She scoots past a knot of clouds, flicking knobs on her dashboard.

The land below looks vast, and for good reason. After Tassie, Melville Island – where we’ll soon land – is reputedly the second-largest island in Oz. Bathurst Island, Tiwi’s other big player, comes in at a respectable fifth.

But all that space hasn’t influenced the head count. Just 2200 people populate the Tiwis; roughly 90 per cent of whom are Aboriginal.

The terrain seems untouched. And that’s because Tiwi’s been isolated from the mainland for so long (Tiwi means the ‘we island’; as in ‘just us’). The first European settlement allegedly set up stumps in around 1830, but things didn’t work out, so it was really the missionaries who first laid roots – and that was just 100 years ago.

Remote but culturally rich Tiwi Islands.

Here at Milikapiti airstrip, a toilet-block-style shelter separates our plane from the dirt road outside. The shelter’s walls are fringed with Indigenous paintings of fish, lizards and crocs.

Beyond these, our chariot awaits: a four-wheel drive sent from the aptly-named local art and craft centre, Jilamara, the first step on our Tiwi Islands art tour.

As we bumble into the township, the streets drift with kids, dogs and women in bright skirts. In the distance, I catch glimpses of the ocean.

A row of artists in paint-flecked T-shirts form a mini welcoming party at Jilamara. They nod their hellos as the gallery manager ushers us inside. The space is crisp, if a little austere. It’s got high ceilings, sliding panels of paintings – and, ah, relief – frosty air con.

Immediately we spot a nook of towering, carved burial poles. They host vertical stacks of animals and teardrop-shaped loops. Each is priced between $500 and $10,000.

The yellow ochre before it becomes art, Tiwi Islands.

Next up: a cove of carved birds and painted shells. “Whenever the artists make an owl [‘book-book’ in the local language], they’re sold straight away. Visitors love them,” says the manager.

As for the bulk of the room, it’s filled with canvasses in traditional designs and colours – no pink, blue or green in sight, just salt-of-the-earth ochre shades: red, white, black, brown, orange and yellow.

We’re introduced to our guide for the morning, artist and artists’ assistant Glen Famer. With tiny crops of grey bundled into his black hair, Glen speaks like a brook – swift and melodic. He lets fly with a litany of info about the art centre, the township, its flock of artists and facts about coffee.

Oddly and fabulously, Glen trained as a barista in Sydney but, despite much coaxing, he won’t flex this muscle for us today. He instead leads us to a deck of drawings by Janice Murray, who’s famous (among other things) for painting one of Layne Beachley’s surfboards.

Jilamara Arts and Craft Association, we soon learn, has the names. It represents the high end of Tiwi art.

The centre is home to works by 2012 Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award winner, Timothy Cook (affectionately called ‘Timmy’) as well as other established figures like Raelene Kerinauia, Patrick Freddy and Conrad Tipungwuti.

The latter is guilty of extreme shyness, and when we pass by his workbench, Conrad flees from his paints, grabs his coffee mug and hides around the corner.

Patrick Freddy, known for his carvings, is a little less retiring. We spot him working away under a huge wattle tree.

“Patrick’s a traditional landowner,” says Glen. “What do you do when you get bored of work, Patrick?” he asks. “Hunting!” replies the artist, flashing us a grin and dipping his sports cap.

“My totem is a seagull,” says Glen, pointing to a lone bird carving lain on the ground. “When I die I will fly away. Seagull. My dreaming.”

I’m not entirely sure what Glen means, but back inside, Tiwi Art Network’s Kerry Digby explains why the scene here is unique.

For starters, wooden carvings – particularly their burial poles – derive from the ‘pukumani’ (funeral) ceremony. The Tiwis often use these in place of gravestones, which seems far more personal and life-celebrating than the Western ritual of plaques and marble.

The Tiwi Islands – a 30-minute plane ride north of Darwin – are famous for their art.

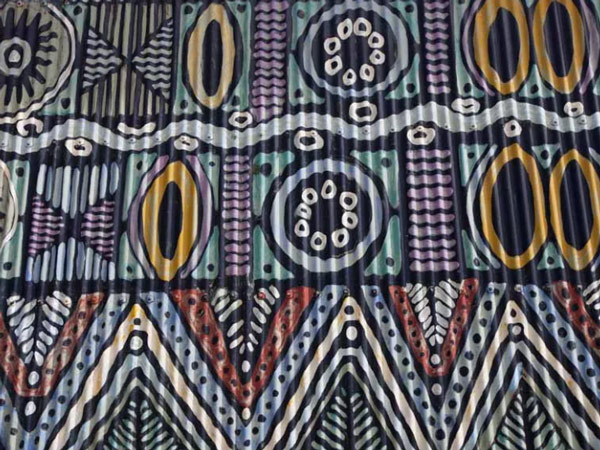

“In Tiwi art, you’ll see lots of cross-hatching, geometrical designs and circles that represent the yam ceremony, ‘kulama’ – an initiation ritual for young men. And the artists also use ironwood combs as paint brushes, a technique that’s often confused with dot painting.”

The gallery manager leans in on our chat. “This isn’t the sort of place where people rush off a bus, buy a shell and bugger off,” he says, in reference to the amount of detail we’re being given. “If they’re making a hefty investment, they want time to think.”

Big money has gone into refurbishing the centre and it’s expected high-end buyers (willing to spend anywhere up to $20,000 – although prices start as low as $50) will go out of their way to get here.

So far, the plan seems to be working. Just this week, investors from Germany and the US have flown in and left with bundles of art in tow.

I imagine corporate customers to be the ideal market for Jilamara’s bold, earthy and original offerings.

I can see pukamani poles donning hotel foyers and Conrad Tipungwuti’s trademark circles swirling above stylish executive desks, or beautifying the walls of an architecture firm.

Each Tiwi Islands’ artwork is intricately made.

Just as compelling as the artworks’ beauty, though, is their meaning. If you’re spending a lifetime with something, you want to know its history and the rituals it’s born from.

It might be a big ask to get art-loving corporates out this far, but one thing is certain: if buyers make the effort, they’ll be rewarded with exclusivity. Mass market, this is not.

After a lunch of sandwiches and soft drinks, we amble through the adjacent art museum, farewell the artists, and then board our 4WD, ready for flight number two. Sarah looks casual about the whole thing, so this time I suck it up, keep quiet and strap into my seat.

Twenty minutes pass and the plane engine whines towards another airstrip. We’re at Pirlangimpi, slightly south of Munupi, for the next stop on our Tiwi Islands art tour.

Waiting to greet us are two barefoot children, Ruby the dog, and Anisha, a young woman with loose curls and a nose ring.

Along with her husband Mike, Anisha manages the Munupi Arts Centre. Here, the vibe is different. It’s island. Throw in some Bob Marley, more colour, more bare feet, and you’re there.

Anisha’s husband Mike, helps his wife manage the Munupi Arts Center.

Anisha doesn’t give us a formal tour but instead lets us wander around the studio, inside the storage cupboards and past the doors of the potter’s quarters.

Today it’s women only – but that’s not the rule. Kids sit with their aunts and grandmas amid messy blobs of paints. Up the back, quieter artists delicately tap away with long, thin brushes.

Marley blends into John Williamson tunes, then, unexpectedly, into the playful 1980s Joe Dolce song ‘Shaddap Your Face’.

“At Munupi we’ve got known senior artists who started painting late in life – they’re special and amazing, but the future lies with their granddaughters,” says Mike.

“This is the art we’re most excited by: that’s done by our group of enthusiastic younger women, using great technique. They’ve been watching their more established relatives for a long time, but now they’re showing what they themselves can make.”

Compared with Jilamara, Munupi has more emerging artists. The price range here is cheaper, too. It tops out at only $10,000. But I notice there’s a fair bit less on display.

Anisha explains apologetically. “We’ve just had an American buyer visit who practically stripped our walls. She bought loads, so we’re looking a little bare.”

Nonetheless, I spot a horizontal canvas, about two metres long, and fixate. It shows a line of five screen-printed trucks in yellows and pinks, each loaded with a different crop of adults, children and dogs. “That one’s called ‘Going to the footy’ and it’s about $600,” she says. Seems it won’t fit in our toy-size boot though. Sigh.

Taking advantage of my slumped figure, Anisha’s youngest girl thieves my pen and notebook. She scrawls me out a picture, then hands back the book. “A headless turtle!” she proclaims.

I coo. “Thank you!”

A wriggling child at Tiwi Designs, Bathurst Island.

Notebook regained, I scribble my review: Munupi is more of a wondrous art shed than a gallery. And I like that.

It’s a place you’d travel to for well-priced, less traditional work – the kind that hums with youthful energy. For practising artists, this would also be an ideal spot to stay a while: sign up for a workshop with a resident artist here, say, or just hang around a while and get inspired.

Our motley crew, Ruby included, tumbles back into Anisha’s van and the Pirlangimpi family waves us farewell. Soon they’re lego figures – tiny dots far beneath us, on a frame filled with circling roads, mint water and streaks of fluro shrubbery.

I glance at Sarah in all her blonde beauty, effortlessly guiding our plane towards the clouds; then fix my eyes on the land below.

As I scour its tapestry for brumbies, owls and pukumani poles, I know the ‘we island’ has revealed just a fragment of its magic today. In this sweep of 11 isles, a parallel world’s doing its thing. I want to see more.

Maybe from a boat. And breathe.

SeaLink Northern Territory operates a return ferry service on Mondays, Thursdays, Fridays and Sundays. Adult return tickets are $120; concession $90; children $65 (under-fives travel free). Tour packages are available through AAT Kings.

Darwin from the ‘jump-seat’ of a small plane returning from a Tiwi Islands Art Tour.

Climate-wise, it’s most comfortable between April and November. But if you can, time your visit to coincide with The Tiwi Islands Football League Grand Final takes place on a Sunday in March every year (although it was delayed till May, post-COVID, in 2022).

With more than 900 participants out of a community of over just over 2500, the Tiwi Islands can claim the highest football participation rate of any community in Australia.

If you want to experience a footy match with real passion, forget about the mainland games – head to a game with a real difference.

In the words of TV presenter David Koch, it’s “a true hoot. Great footy skill and a huge communal party. The three religions here – footy, art and churchy stuff – come together in the Tiwi’s biggest day out of the year.”

Spectators at the Tiwi Islands Football Grand Finals.

The Tiwi Islands Football League Grand Final takes place in the sweltering afternoon heat on a Sunday in March in Nguiu (pronounced new-you), the main settlement on Bathurst Island, and attracts visitors from Darwin and beyond, who swell the crowd for the game to nearly twice the island’s population.

The 5000-strong crowd typically cheers on both sides, in an encounter where the football is fast and furious.

During the quarter breaks the field fills with young Tiwi children, the stars of the future, for your classic kick-to-kick. Named as one of the ‘100 Things to Do in Australia Before You Die’ in Australian Traveller’s inaugural bucket list the day is a celebration of all things Tiwi, including the morning Tiwi Islands Art Sale.

For the  best travel inspiration delivered straight to your door.

best travel inspiration delivered straight to your door.

LEAVE YOUR COMMENT